When Machines Outplay Us: The Unintended Renaissance of Chess

While new technologies that mimic human abilities can be unsettling, the history of chess and technology suggests a future of optimism rather than doom.

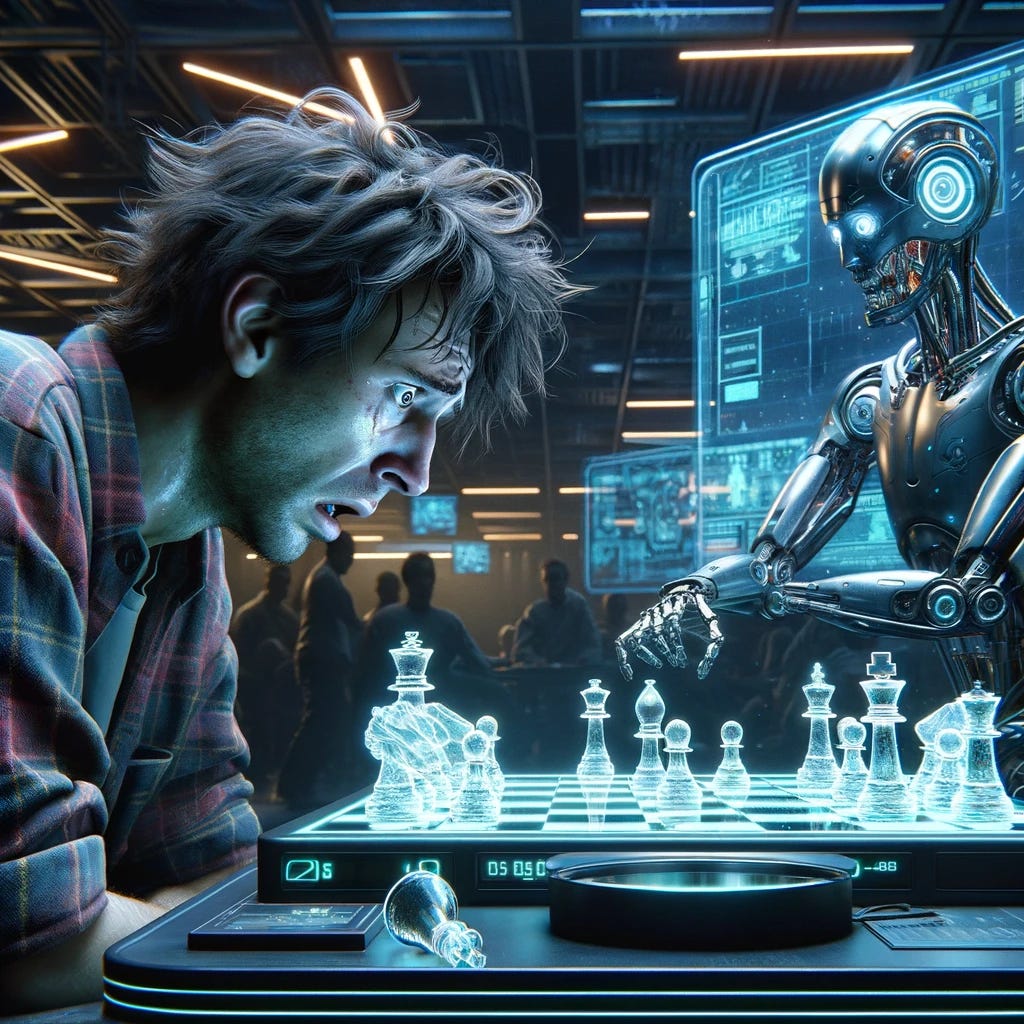

It was the ultimate man-vs-machine showdown. Garry Kasparov, the reigning chess master, had already shown that no machine could beat a human in the ultimate game of strategy: chess. However, the engineers at IBM kept improving Deep Blue, and in a highly anticipated event in 1997, the machine finally triumphed over humanity. Deep Blue won against Kasparov 3½–2½. It was a landmark moment, heralding the rise of AI.

If machines can beat us at chess, why should we even bother playing? Humans are a fiercely competitive species, having outlasted the other eight species of the genus Homo. Unlike other animals, we didn't coexist with our close relatives; we dominated. This competitive drive, ingrained in our DNA, has propelled us to build cities, travel the world, and use technology to improve our lives. But it also makes us paranoid about any potential competition, fearing not only for our lives but for the future of humanity.

The logic seems sound: if machines can surpass us, we should stop their advancement. When it comes to chess (which some argue is more than just a “game”), the results might seem harmless. The machines win, we stop playing, and life goes on. Right? Maybe we just switch to playing Go, that seems like a safe choice.

But… if the machine can beat us at chess, how long until it can beat us at anything?

Oh, I can feel the paranoia creep back in. Why didn’t we just destroy Deep Blue back in 1997 and ban all development in AI? That would save humanity for sure.

The problem is, this us-vs-machines mindset is flawed. We apply the same competitive logic we've used against other humans and life forms to machines. However, machines don't strive for survival. They don't need resources or worry about offspring. Machines are tools, and history shows that better tools lead to better lives.

So what happened after Big Blue beat Kasparov? Well, we didn’t destroy the machine, thank god. We did worry about the future of chess, and many predicted the game would soon become obscure if not obsolete. But those predictions were wrong. Completely wrong.

Even though the event was staged as a competition between human and machine, it was more for the spectacle. In reality, no one cares if a computer can beat them at chess, just like we don't mind that cars are faster than us. Actually, we do care—because faster cars mean we can travel quickly with less effort. Similarly, better chess tools have made the game more accessible and enjoyable.

When I was growing up in the 80s I dabbled with playing chess, but it was hard. My family owned a book about chess that covered the basics and some intermediate tactics, but if I wanted to practice I either had to convince a friend to play a game or join a local chess club which would yield maybe an hour or two each week of actual playtime. And let’s imagine I had become really good, it would have become increasingly harder (and probably impossible given that I lived in a small island in the North Atlantic) for me to find opponents that challenged me and helped me improve even further.

That’s no longer the case. If you are interested in chess, all you need is a mobile phone and you can spend as much time as you want playing opponents at any level. You can even play puzzles and challenges created by machines to improve certain aspects of the game, making the whole journey even more fulfilling and fun.

Machines didn’t kill chess by beating us, they made it wildly more popular and accessible. Chess players around the world still enjoy playing with each other but the barrier to entry has gone so much down that anyone can enter.

It’s hard to find good numbers on how many people play chess on a regular basis, but a survey from 2012 put it at around 600 million people worldwide. That’s around 8.5% of the world population at the time! And as an indicator of the growing popularity of chess, between 2009 and 2014 the number of active chess players with a FIDE rating almost doubled. These statistics are over a decade old, and chess’s popularity just keeps rising, thanks to machines getting better at it.

History has shown that we tend to panic when things seem to threaten us. The most famous example was the Luddites who revolted against textile machines in the early days of the Industrial Revolution. People were naturally scared; suddenly, a machine became an expert at their livelihood. But history has repeatedly shown that inventing new tools has consistently made our lives better.

Should we be afraid that Google knows more facts than any human in the world? Or that the mobile phone can help us find a nearby driver, tell them our location, and handle everything from navigation to charging for the ride? The list of things technology can do for us is endless, and they are by design things we cannot do as well without these inventions.

Why is AI so different?

AI, like all technologies before it, is a tool—one that has the potential to enhance our capabilities and improve our lives. Instead of fearing its rise, we should embrace it while remaining vigilant about its ethical implications. Deep Blue's victory over Kasparov didn't mark the downfall of humanity; it showcased our ability to innovate and adapt. Today, AI is making chess more accessible, learning more intuitive, and problem-solving more efficient.

Rather than seeing AI as a competitor, we should view it as a collaborator—one that can push us to new heights of creativity, productivity, and understanding. The future of AI is not a zero-sum game where machines win and humans lose. It's a symbiotic relationship where both can thrive.

So, let's not destroy our Deep Blues. Let's build them, refine them, and use them to unlock possibilities we never imagined. In doing so, we might just find that the greatest victories are not won on a chessboard but in the limitless potential of human ingenuity amplified by the tools we create.

You might consider this perspective, Gummi: https://www.currentaffairs.org/news/2021/06/the-luddites-were-right